I’ve spent years watching the tech industry shrug its shoulders at the Global South. The excuse is always the same. “We’d love to support those languages,” they say, wringing their hands, “but there just isn’t enough data.” It’s a clean, convenient narrative. It’s also dead wrong.

We aren’t dealing with a scarcity problem. We are dealing with a logistical nightmare.

The data for South Asia’s languages—spoken by a quarter of the human population—isn’t missing. It’s just buried. It sits in dusty university basements, trapped in out-of-print journals, or scribbled on decaying palm leaves. Leading researchers have finally started calling this what it is: Data Scatteredness.

The information isn’t a ghost; it’s a puzzle piece kicked under the rug. And until we get on our hands and knees to find it, the digital divide will keep widening.

1. The Internet is an Echo Chamber. The Real Data is Offline.

There’s a massive misconception that if Google can’t find it, it doesn’t exist. This is dangerous thinking.

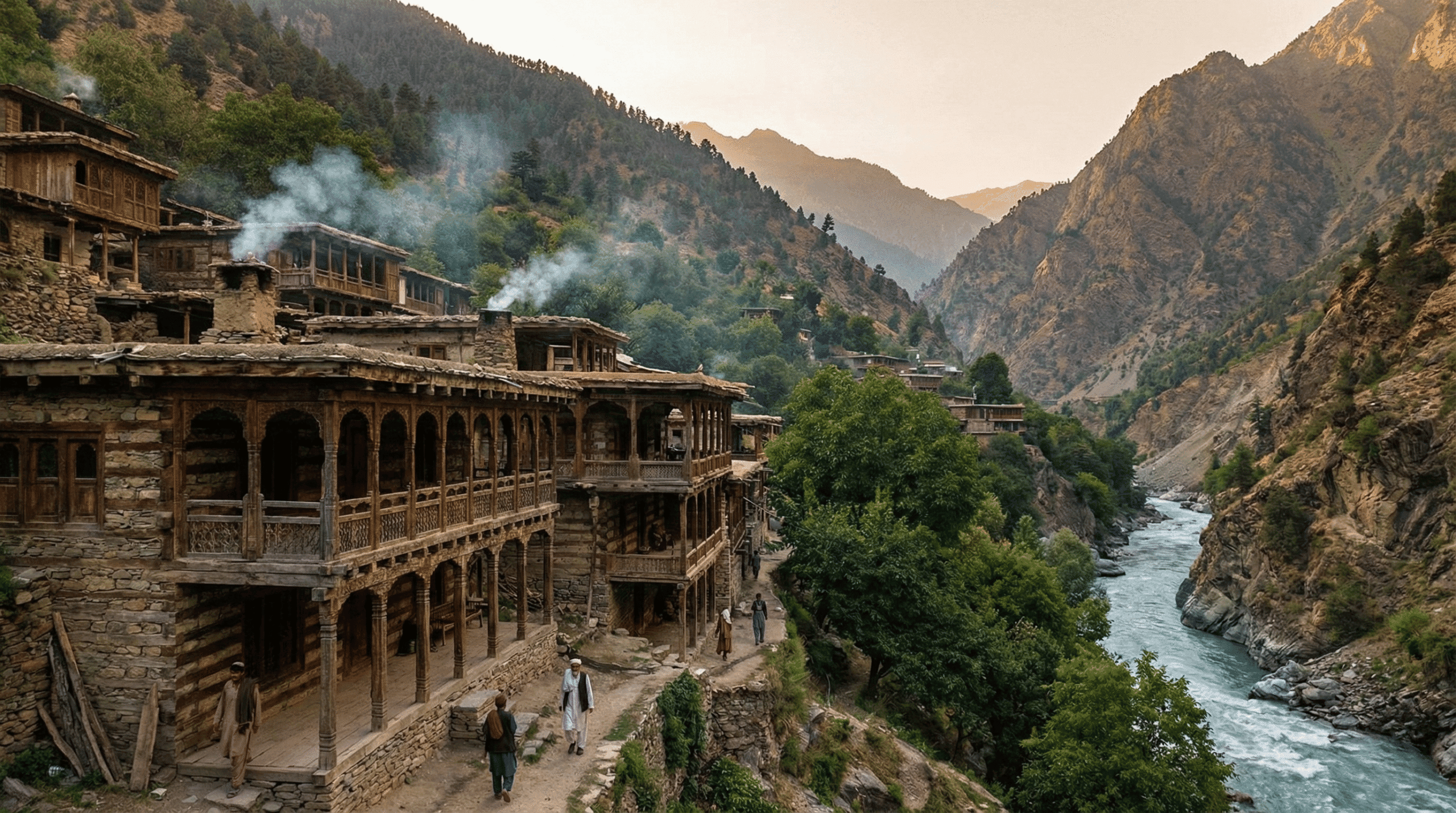

In my experience analyzing “low-resource” languages, I’ve found that the term itself is often a misnomer. Take Burushaski. It’s a language isolate in northern Pakistan, completely unrelated to any other human tongue. You won’t find a massive Common Crawl dataset for it. But does that mean the data is gone? No.

It exists in decades of meticulous work by field linguists. Detailed grammars. Folk tales. Treebanks for languages like Palula and Toda.

The problem isn’t creation; it’s extraction. We don’t need to generate new text; we need to perform digital archaeology. We have to take physical, analog brilliance and drag it, kicking and screaming, into the machine-readable world.

2. To Build the Future, We Must Loot the Past

Here is the irony that keeps me up at night. The solution to cutting-edge AI isn’t finding new tweets; it’s reading ancient rocks.

Computational historical linguistics is the unexpected hero here. Why? Because historical linguists are obsessive. They don’t just read text; they structure it. They map the evolution of grammar over centuries.

Look at the Ashokan Prakrit project. Researchers are currently building a “treebank” from inscriptions carved into stone pillars in the 3rd century BCE. Think about that. We are using 2,000-year-old rock carvings to train the neural networks of 2026. It sounds absurd. But it works. By analyzing how these languages used to work, we give the AI a structured framework to understand how they work now.

3. South Asia is a Linguistic Riot, Not a “Tapestry”

Let’s cut the poetic fluff. South Asia isn’t a “mosaic.” It’s a chaotic, collision-heavy intersection of four distinct language families—Indo-European, Dravidian, Austroasiatic, and Sino-Tibetan—plus a handful of isolates that defy classification.

For a linguist, it’s heaven. For a developer, it’s a migraine.

The sheer density of variation here is staggering. You have languages that have been borrowing words from each other for millennia, creating a complex web of “cousins” and “neighbors.” This isn’t just diversity; it’s noise. High-fidelity, beautiful noise. Organizing this mess is the single greatest challenge in Natural Language Processing today.

4. When Grammar is Music, Not Math

Here is where the AI usually breaks.

I remember the first time I looked at the “Kalami-type” languages of northern Pakistan, like Gawri and Torwali. My brain stalled. In English, if I want to make a word plural, I add an “s.” Simple. Linear.

In these languages? You sing it.

They use phonemic tone—pitch changes—to mark grammar. The difference between a man and a woman, or one object and many, isn’t a suffix. It’s a musical note. This terrifies standard AI models. They look for text strings, not sheet music. If we want machines to understand these people, we have to teach them that grammar isn’t just spelling. It’s sound.

5. The Jambu Project: A Digital Rosetta Stone

So, how do we fix it? We stop working in silos.

Enter the Jambu project. It’s a massive, cognate-based lexicon that tries to map this chaos. Think of it as a family tree on steroids. It connects 202,653 words across 294 distinct languages and dialects.

This matters.

It matters because it allows us to use “transfer learning.” If the AI understands Language A, and we know exactly how Language B is related to it via Jambu, the AI can make an educated guess about Language B without needing a billion sentences of training data. It’s a shortcut. A cheat code for low-resource languages.

The Bottom Line

We are sitting on a goldmine of human culture, and we’re complaining that we don’t have a shovel. The data is there. The methods exist. The only thing missing is the will to get our hands dirty.

So, are we going to let these languages die in silence, or are we going to start digging?