Most people think of astronauts as polished, untouchable figures waving from a gantry. But if you’ve spent any time covering the actual operations of human spaceflight—as I have, watching launches turn into delays and then into ordeals—you know the reality is sweatier, messier, and far more bureaucratic.

Sunita Williams just retired.

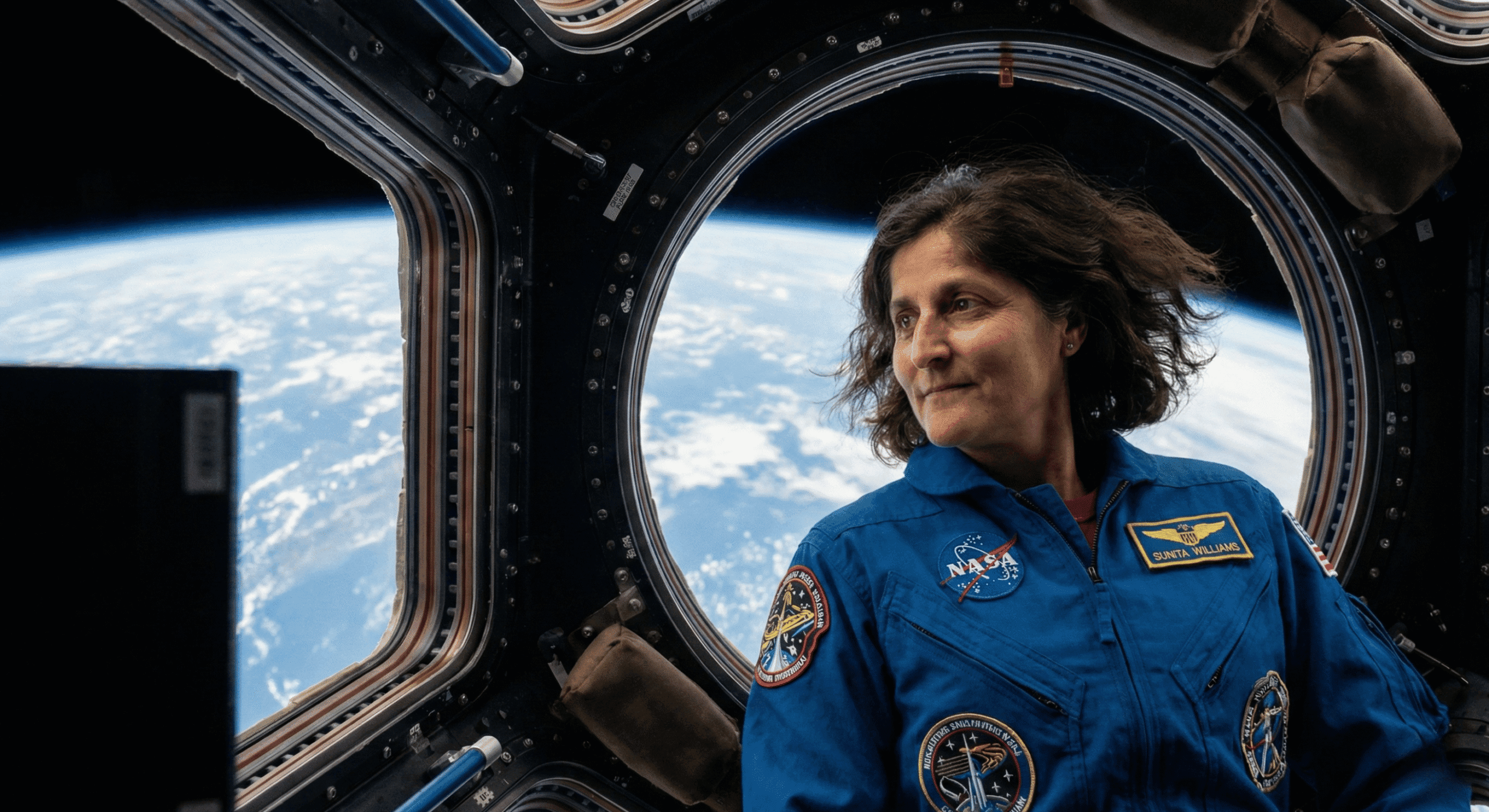

Twenty-seven years. Three missions. A staggering 608 days off the planet. But if you focus on the shiny medals, you miss the point. The real story isn’t the records. It’s the grind. It’s the fact that her career didn’t end with a parade, but with a logistical nightmare that would have broken a lesser operator.

Here is the truth about what it actually takes to survive in orbit, stripped of the NASA press release gloss.

The “Eight-Day” Trip That Lasted a Year

Let’s be honest about the Starliner mission. It was supposed to be a sprint. A quick “up-and-back” to certify Boeing’s bird. Pack light, check the systems, come home for dinner.

That’s not what happened.

Instead, Williams and Butch Wilmore got stuck. Real stuck. The thrusters acted up, the helium leaked, and suddenly, a week-long shakedown cruise morphed into an eight-month marathon aboard the ISS.

I can’t overstate the psychological toll of that pivot. Imagine going on a business trip for a weekend and being told you can’t come home until next year. And oh, by the way, you didn’t pack enough underwear.

This wasn’t just a delay; it was a siege.

Williams didn’t buckle. She didn’t vent on the comms. She simply clocked in. That ability to flip the switch from “test pilot” to “long-haul tenant” is rare. It’s not something you learn in a classroom; it’s a temperament you’re born with. It felt less like a space mission and more like a submarine deployment that refused to end.

Smashing the “Gendered” Ceiling of the Spacewalk

I remember the old guard talking about EVAs (Extravehicular Activities) like they were purely a test of brute strength—a man’s game. The suits are pressurized beasts; fighting against them to turn a wrench is exhausting. It feels like squeezing a tennis ball every second for six hours.

Williams didn’t just participate in that game; she rewrote the rulebook.

She logged 50 hours and 40 minutes in the void across seven spacewalks. She didn’t do this to make a point. She did it to fix the station.

And then there was the marathon.

Running 26.2 miles is hell on Earth. Running it while strapped to a treadmill with bungee cords so you don’t float away? That’s masochism. But she did it in 2007. Why? Because the mental decay of isolation is real, and sometimes you have to manufacture your own finish line just to feel alive.

The Pilot Who Happened to Be an Astronaut

Before she was a space hero, Williams was a Navy captain. She flew H-46 Sea Knights.

If you know anything about military aviation, you know the H-46 isn’t a luxury ride. It’s a workhorse. It rattles your teeth. She racked up 3,000 flight hours in over 30 different aircraft. She wasn’t sitting in a simulator; she was flying relief ops during Hurricane Andrew and support missions for Desert Shield.

This matters.

When the Starliner started throwing error codes, Williams didn’t panic. Why would she? She’s used to flying heavy metal in bad weather. That operational discipline—the kind forged in the chaos of a disaster zone—is the only reason the Starliner drama remained a technical issue and didn’t become a crisis. She treated the spacecraft like a malfunctioning helicopter: troubleshoot, stabilize, survive.

The Federal Employee Reality Check

Here is the part that always makes me chuckle.

We treat astronauts like gods. We put them on pedestals. But when Sunita Williams punched out for the last time, she didn’t get a superhero’s exit package. She retired under FERS—the Federal Employees Retirement System.

That’s right. The woman who commanded the International Space Station gets a pension calculated the same way as a frantic HR manager at the Department of Agriculture.

It grounds the myth, doesn’t it? It reminds us that for all the glory, this is public service. It’s a government job. You file paperwork. You deal with bureaucracy. You get a standard “high-3” pension calculation.

And frankly, I love that.

It strips away the “visionary” nonsense and leaves us with the raw truth: Sunita Williams wasn’t a magician. She was a dedicated, hyper-competent civil servant who just happened to work 250 miles up.

The Bottom Line

Space isn’t glamorous. It’s dangerous, uncomfortable, and often boring. Sunita Williams thrived not because she chased headlines, but because she understood the work. She embraced the suck.

As we look toward Mars—a trip that will make an eight-month delay look like a nap—we need to stop looking for show ponies. We need more workhorses. We need more people like Sunita.